Residents on Ocracoke Island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks first heard the sound on the night of 23 January 1942. It came from offshore and was almost loud enough to shake the house.

The room would light up and you’d go out and see that a ship had been destroyed

“You’d be sleeping in your room and would hear this dull roar,” said Joseph Schwarzer II, director of North Carolina’s Maritime Museum System . “The room would light up and you’d go out and see that a ship had been destroyed.”

That ship was the British tanker Empire Gem, which had been torpedoed by a German U-boat. Over the next six months, Ocracoke residents heard more noises and saw more debris, as the Germans launched their Operation Drumbeat blockade.

For most people in the US, World War Two happened thousands of miles away. The closest they came to a battle was the nightly radio report, learning about places like Guadalcanal or Normandy, where men fought on warships or stormed beaches. But for residents of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, the war was much closer to home.

For residents of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, World War Two was close to home (Credit: Spring Images/Alamy)

During Operation Drumbeat, Germany targeted merchant ships leaving US ports, as many of them were heading for the UK. Even before the United States entered the war, shipments were going out from East Coast ports on a regular basis, delivering items like food, aluminium, steel and rubber to help support the UK’s war effort.

You may also be interested in: • The top-secret meeting that helped win D-Day • How Crete changed the course of World War Two • The nine ghost villages of northern France

While the US was officially neutral, Germany couldn’t openly attack the ships leaving East Coast ports with these supplies. That changed in December 1941, when Germany and Japan declared war on the United States. One month later, the U-boats arrived on the East Coast and started targeting ships right off Ocracoke.

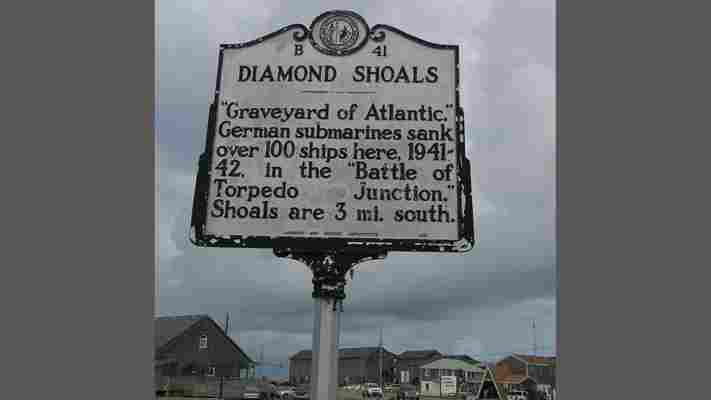

“On the North Carolina coast, you have its Diamond Shoals, sandbars that ships want to avoid,” said Dr Frank Blazich, lead curator of military history for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History . “Ships would be hugging the coast and then shooting out to avoid the shoals, which made for a perfect chokepoint. The U-boats could hide and just have a field day, firing away.”

And fire away they did. In January 1942 alone, U-boats sank 35 Allied ships off the East Coast. To put that in perspective, an average ship leaving the US carried enough supplies to feed England for more than a day, according to Dr Schwarzer. When you add up just those 35 ships lost in January 1942, it would have been more than enough to feed England for a month.

Supply ships departing North Carolina ports had to navigate the Diamond Shoals, making them easy targets for German U-boats (Credit: Jason O. Watson/historical-markers.org/Alamy)

I got a look at some of the destruction on my own way to Ocracoke. While waiting for a ferry from nearby Hatteras Island, I stopped in at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum . It paints a clear picture of the damage done during Operation Drumbeat, as well as the larger story of the war in the Atlantic from 1942 to 1945, through exhibits of wreckage from the ships as well as photos, both above and below the water, of shipwrecks from the battles.

A lot of times, students stepped over debris on their way to school

Ocracoke residents got to see some of that damage first hand. They didn’t just see the lights and hear loud noises as U-boats attacked. Because the boats came so close to shore, residents also saw debris from wrecked merchant ships.

“A lot of times, students stepped over debris on their way to school,” Dr Schwarzer said. “They walked right past it and in some cases over it.”

Paying tribute

I’d come to the island to see a permanent reminder of the cost of battle. Every year, on a mid-May weekend, the US Coast Guard and the Royal Navy hold a ceremony on a portion of Ocracoke Island that is permanently leased to Britain, a tiny patch of land where four English sailors are buried.

I’d been told to look for the Union Jack. It was hard to miss, residents said, with trees on one side and houses on the other. I turned right off Irvin Garrish Highway, Ocracoke’s main road, heading for 234 British Cemetery Road.

In January 1942, U-boats sank 35 Allied ships off the East Coast (Credit: MPI/Getty Images)

As it turned out, the site was pretty easy to spot. I could see the flag just off the right side of the road behind a beautiful scene with flowers and a monument. As I parked the car and walked over, I could also see tombstones, enclosed by a white picket fence. These are the graves of four men: 24-year-old Londoner Stanley Craig; 27-year-old Blackpool resident Thomas Cunningham; and two of their shipmates who have never been identified, who are all buried here.

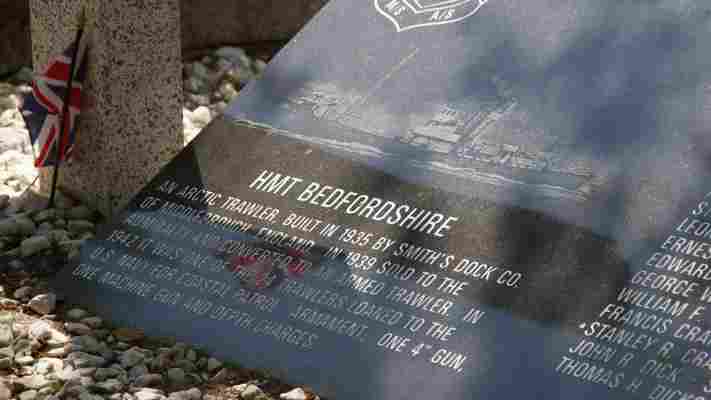

Next to them was a list of 37 names on a plaque, all crew members of the HMT Bedfordshire. There was 18-year-old Canadian Russell Samuel Davis, who had joined the war as part of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve. There were sailors from across the UK on the list too, including 21-year-old Surrey native William Frederick Clemence, 32-year-old Girvan local John Rowan Dick and 31-year-old Brecknockshire resident Frederick William Barnes, among others.

Also on the plaque were words from the poem 1914 V: The Soldier by British World War One soldier Rupert Brooke:

“If I should die, think only this of me/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is forever England.”

Today, a small patch of land on Ocracoke Island where four English sailors are buried is permanently leased to Britain (Credit: Brian Carlton)

But why is there a memorial to the crew of British ship on a North Carolina island? It has to do with those loud noises Ocracoke residents heard – and the plan to make them stop.

Stopping the U-boats

Tired of seeing merchant ships sink and unable to provide protection, US president Franklin Roosevelt reached out to the UK. Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered 24 ships to patrol the US East Coast, sending over private ships that had been called into service.

“The Admiralty was able to send over 24 vessels of the Royal Navy Patrol Service,” said Commodore Andrew Betton, UK Naval Attaché, who was at the ceremony. “Those 24 vessels came over largely crewed by the original trawler men, with a few additional Royal Naval Reserve gunners, navigators and commanding officers.”

One of them was the Bedfordshire, to which Cunningham, Craig and the rest of their crew were assigned. Originally a deep-sea fishing trawler, the Royal Navy bought the Bedfordshire in August 1939 and outfitted it with a sonar system, a four-inch deck gun, a .303 caliber Lewis machine gun and 80 to 100 depth charges. Before long, the ship was a seasoned U-boat hunter, chasing off German ships from the UK on a regular basis.

Then, in February 1942, the assignment changed. The Bedfordshire was sent to the Outer Banks to help break up the blockade.

Stanley Craig, Thomas Cunningham and two unidentified sailors were aboard the HMT Bedfordshire, which was sunk by a German U-boat (Credit: FOR ALAN/Alamy)

A final post

For two months, the Bedfordshire patrolled the Outer Banks, helping with salvage operations and searching for U-boats. Then, on 11 May 1942, the hunter became the hunted. Bedfordshire and fellow trawler HMT St Loman, also part of the Outer Banks patrol, U-boat found them first. U-558 fired torpedoes at both ships and hit the Bedfordshire, sinking the ship with all crew lost.

Because it happened so fast, there was no time to send out a distress call. In fact, it would be days before anyone knew what happened to the Bedfordshire, when the bodies of four men washed up on Ocracoke on 14 May. Out of those four, only Cunningham and Craig could be identified.

This memorial and gravesite in North Carolina will forever be considered British soil

Normally during wartime, a soldier's body is shipped home to his family. Due to the island's isolation, however, there were limited supplies on Ocracoke in 1942, including a lack of materials needed to preserve bodies. As a result, all four men had to be buried quickly on the island. To pay respect to the Bedfordshire's crew, Ocracoke residents also built a monument as part of the cemetery, giving all four men full military honours.

“The cemetery on Ocracoke is the only one in deeded to the British,” Dr Schwarzer said. “The island residents (and North Carolina) said let’s give this land in perpetuity to Britain.”

The land was leased to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which keeps track of and maintains all graves of soldiers who died in either of the two World Wars. And since it was granted ‘in perpetuity’, this memorial and gravesite in North Carolina will forever be considered British soil.

Every May, a ceremony is held at Ocracoke’s British Cemetery to honour the sailors who served on the HMT Bedfordshire (Credit: FOR ALAN/Alamy)

At the ceremony, I watched as wreaths were placed on the memorial to honour the sacrifice of the Bedfordshire’s men, while the US Coast Guard Pipe Band played. The American and British Royal Legion Riders, veterans who hold motorbike rides to raise money for wounded soldiers and other charity projects, conducted a special tradition as they do every year: each group brought a container of water, one from the Outer Banks and another from the UK, and blended them together to symbolise how Ocracoke and the UK are linked. Afterwards, the names of each member of Bedfordshire’s crew was read out, before a 21-gun salute closed the ceremony out.

I took off my baseball cap as I stood by the graves, reflecting on history. Thirty-seven men left home to defend people in another country, giving their lives to do so. That truly deserves respect and honour. It seems fitting that the Bedfordshire’s crew is not forgotten, but honoured in ‘some corner of a foreign field.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article has been revised to clarify that the land was leased to Britain, not England, and that entire UK was involved in the war efforts.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Leave a Comment