Article continues below

It was on a grey winter’s day in my parents’ house outside Glasgow, watching storm clouds gather and sparrows dive for shelter in the garden, that I first suggested Mont Blanc in summer. After what had happened, I knew I should make more effort to spend time with my 74-year-old dad, but what I was proposing at his age was a risk. A 10-day hike around one of Europe’s highest mountains seemed a little extreme.

“Old age doesn’t come alone,” he replied, implying the aches and pains, arthritic hands and memory loss from a recent life-threatening stroke couldn’t be ignored.

He glanced at me with a fatherly look, suggesting he knew better. I wondered if he could make it. In his youth, unquestionably; but now I wasn’t so sure. Perhaps a trip hiking Mont Blanc’s steep-faced valleys, following a hut-to-hut trail through France, Italy and Switzerland, was already past him.

Author Mike MacEacheran hiked the Tour du Mont Blanc with his 74-year-old father (Credit: Mike MacEacheran)

You may also be interested in: • Where doing nothing is a way of life • The code that travellers need to learn • A town that sold mountains to the world

Now a grandfather, he had spent his best years in the Alps – summer after summer, in fact – and to take him along this pathway in search of a route to his past, to stir memory in long-forgotten footprints, seemed like the right thing to do.

“You’ll remember the mountain refuges are beautiful,” I said casually, compelled to disturb what lay hidden in his memory. “That’s half the reason for going.” It was shrewd of me to work in the idea of fondue, red wine and good company; we booked a flight, and four months later, arrived in the shadow of Mont Blanc (4,807m) in Chamonix, France.

The Tour du Mont Blanc is a challenge for anyone, regardless of age, condition or state of mind. A bucket-list pilgrimage for long-distance hikers, it is a 170km, high-altitude journey on foot, a ritual walk through great landscapes and drama that plugs hikers in to something unquantifiable, yet life-affirming. While I travelled for a love of people, food, drink and culture, my father had always been drawn to places that weren’t as easily accessible. The mountains appealed because of their unreachability. Hikers, he once told me, came to learn about themselves.

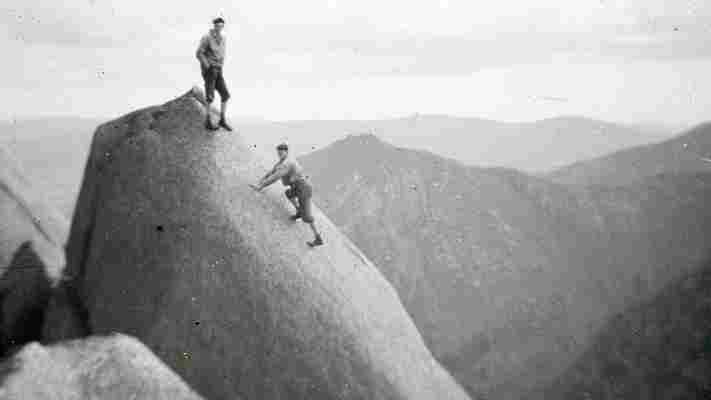

MacEacheran’s father spent his youth summiting peaks throughout the Alps (Credit: Mike MacEacheran)

That first sunlit afternoon, it was instantly obvious we’d made the right decision. The pathway ahead was quiet, little more than a few bell-clanging cows, a couple of errant dogs, a rosy-cheeked French farmer en route to his summer cottage. Hedgerows and thickets of wild Alpenrose lined the trail’s edges. On the horizon, stone-faced peaks sat above the plateau, skirted by pine forests and chequerboard fields. Quick-footed hikers trotted past us, eyes focused on a ridge that marched south to the Italian border. But there was no sign of worry etched on my hiking partner’s brow. Only determination.

My dad’s hazy accounts of his time in the mountains remain among the defining stories of my childhood. The first time it left an indelible mark was when flicking through a junk box full of projector slides taken circa summer 1970, when he and two friends completed a previously untried route up the notoriously dangerous North Face of the Eiger (3,970m) in Switzerland’s Bernese Oberland. At the time, he was 27 and to scale the final 1,829m North Pillar wall on the way to the summit was unthinkable. The extreme highs and lows were not easy for him to recount. Along the way, he suffered frostbite, dealt with unexpectedly bad weather and bivouacked night after night in sodden climbing gear on treacherous, ice-coated vertical slabs. Afterwards, he was quoted by The Herald newspaper, the expedition’s sponsor, saying: “I'll never set foot on that bloody mountain again in my life.”

What I’d always seen as an unhealthy obsession with the mountains revealed itself to be a bond I never knew we had

Still today, it’s almost inconceivable for me to comprehend.

In those days, there were other equally spellbinding tales, most of which took him to the Chamonix valley. He summited the Grandes Jorasses (4,208m) in blinding sunshine. He scaled the ice walls of the Aiguille du Chardonnet (3,824m). Hell, on one occasion, he even posed atop the remarkable Aiguille du Grépon (3,482m), a fist of angular rock crafted like a church spire – an exploit that would test the mettle of even the most carefree climber. To an eight-year-old boy, these were unforgettable adventures, shaping my travel perceptions in years to come.

That was now more than half his lifetime ago. And, yet, here we were, marching side by side around the Mont Blanc massif, tracing an invisible route with our fingers over the same harsh and elemental summits he’d conquered long ago. What I’d always seen as an unhealthy obsession with the mountains revealed itself to be a bond I never knew we had.

The Tour du Mont Blanc is a 170km bucket-list pilgrimage for long-distance hikers (Credit: Mike MacEacheran)

As day one drifted into days two and three, we crossed from France into Italy, over the Col de la Seigne, a crested hilltop long an ancient gateway for shepherds to the Aosta Valley. The southern aspect of Mont Blanc and its fraternity of Italian-set buttresses and peaks – Punta Baretti, Picco Luigi Amedeo, the Grand Pilier d’Angle – were spectacular, and had him reminiscing over a glass of wine in the resort of Courmayeur on our third night. Never one with words, he was hard-pushed to explain why these landscapes meant so much to him. Words failed and he shook his head as if to free a lost memory.

The days passed and began to take on a predictable rhythm, the path carrying us ever forward. We rose late, left later (stalled by having to medicate my dad with a daily dose of pills), stopped for lunch then enjoyed a beer on the back of a farmer’s wagon. Finally, after some 20km of up and downhill slog, we’d reach our stop for the night, long after everyone else, but just before stillness descended upon the valley.

“Wait for your old man,” he’d sigh, struggling to catch his breath. “We’ll get there eventually.” And yet this ticking time bomb soldiered on. The base-camp beard and summit gleam from the 1960s had disappeared, but the smile stayed put.

Mike MacEacheran: “There was that smile, those eyes fixed on the horizon, the beautiful Alpine ridges of Mont Blanc crowding out the background” (Credit: Mike MacEacheran)

By week’s end, now back in France after more than 150km through the Swiss farmstead villages of La Fouly and Champex, I sensed we may have achieved what we both had thought impossible. We made our final push towards the Col du Brevent above the Chamonix valley, side-stepping along a devilishly narrow path, then tackled a series of unforeseen rudimentary ladders bolted into the rock, my dad enthusiastically swearing with every rung. It was an apt final hurdle. We climbed up into a narrow world of stone, light and echo, meeting Mont Blanc face on. An ailing Scottish grandpa in good company with the grandfather of the Alps.

To capture the moment, I took a family portrait, but only then did it dawn on me it was nearly the same composition as on a slide I’d first seen in one of those junk boxes, taken almost 50 years ago. There was that smile, those eyes fixed on the horizon, the beautiful Alpine ridges of Mont Blanc crowding out the background. For a split second, it looked like nothing had changed.

Travel Journeys is a BBC Travel series exploring travellers’ inner journeys of transformation and growth as they experience the world.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Leave a Comment